A discovery about how water behaves on one of the world’s thinnest 2D materials could lead to major technological improvements. The future looks intriguing for anti-icing coatings, self-cleaning solar panels, next-generation lubricants and energy materials.

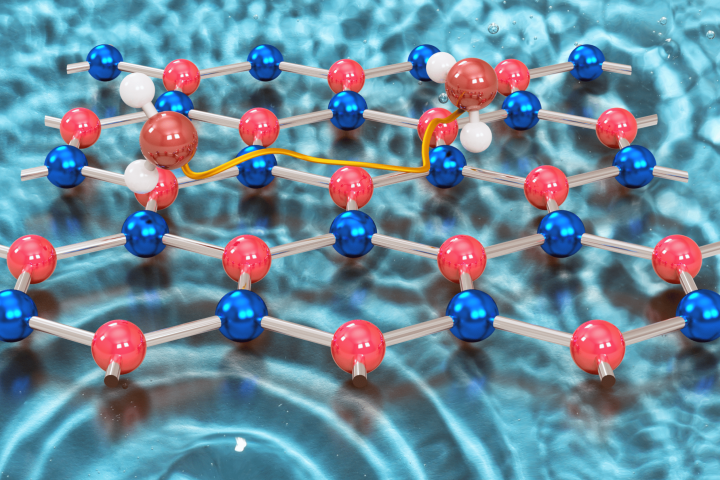

Researchers from the University of Surrey and Graz University of Technology tested two ultra-thin, sheet-like materials with a structure likened to honeycomb in a study published in Nature Communications. The first, graphene – electrically conductive, making it a significant contender for future electronics, sensors and batteries. The second, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), often called ‘white graphite’ – a high performance, ceramic material and electrical insulator.

Researchers discovered that this tiny structural tweak completely changes how water behaves on the surface. Instead of hopping between fixed points, as it does on graphene, water molecules on h-BN glide in a smooth, almost walking motion.

The finding reveals just how dramatically a minute atomic shift can reshape water’s movement at the nanoscale – opening new possibilities for engineering surfaces that master friction, wetting and even ice formation.

Dr Marco Sacchi, Associate Professor at the University of Surrey, and co-author of the study, said:

“We tend to think of water as simple, but at the molecular level, it behaves in remarkable ways. It’s almost like the molecule is walking rather than hopping. This continuous, rotating motion was completely unexpected. Our work shows that the tiniest details of a surface can change how water moves – something that could help us design better coatings, sensors and devices.”

The Graz team captured the moment using a highly sensitive technique called helium spin-echo spectroscopy, which can track the motion of individual molecules without disturbance. Researchers at Surrey also ran advanced computer simulations to model what was happening at the atomic level.

Together, the experiments and simulations revealed that water encounters far less friction on h-BN – especially when the material sits on nickel – allowing molecules to move with much greater freedom. On graphene, however, the supporting metal tightens the grip between the surface and the molecule, boosting friction and slowing water’s motion.

Dr Anton Tamtögl, Senior Researcher at Graz University of Technology, and co-author of the study, said:

“The support beneath the 2D material turned out to be critical – it can completely change how water behaves and even reverse what we expected. If we can tune how water moves with the right choice of material and substrate, we could design surfaces that control wetting or resist icing. These insights could transform technologies that rely on manipulating water at the nanoscale – from advanced coatings and lubricants to desalination membranes.”

The study also highlights the power of international collaboration, with early-career researchers Philipp Seiler, Anthony Payne, Neubi Xavier Jr., and Louie Slocombe playing key roles across both the experimental and computational breakthroughs.