What connects the most watched television series ever streamed on Apple TV, and a collection of Victorian lampposts in Kent?

To answer that question is to do two things that need warning. The first, is a warning for spoilers for the entire first series of what has been one of 2025’s most watched and exciting streaming offerings. The second, is a warning about some upcoming fundamental questions of life, the universe, and everything.

Before we get into the popular television spoilers, let’s talk about what is happening in Canterbury.

A petition has been signed by over seven hundred and fifty residents of the city opposing Kent County Council’s plans to remove many of the cities historic iron cast lampposts.

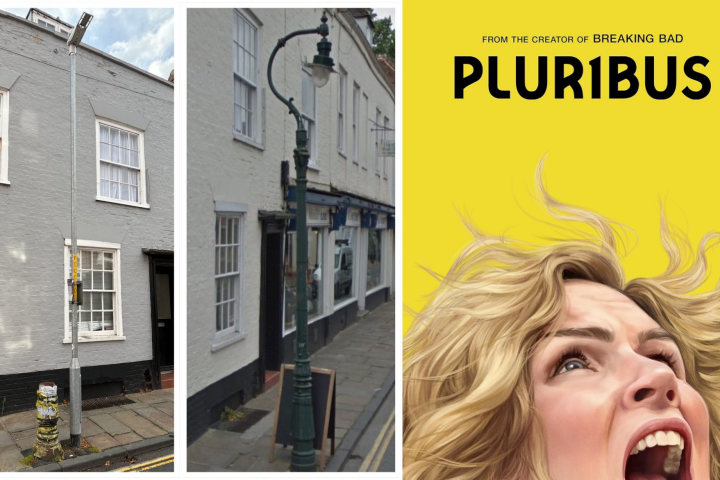

The Biggleston lampposts, identifiable in large part by their graceful swan neck design at the lamp top section, were cast iron works of civil street furniture art that were provided to the city for almost 130 years, before the company that manufactured them went bust in 1963. Approximately 270 such lampposts continue to illuminate the Chaucerian city’s streets to this day, lighting the way for students, shoppers, and generally anyone else moving through the historic county-capital’s centre.

Guy Mayhew, co-chair and campaign co-ordinator of the Canterbury Society, told The Independent: “These columns are part of the city’s everyday historic fabric, not decorative extras.”

Yet now, because of health and safety concerns surrounding the lamppost’s stability, the Reform-led Kent County Council is looking seriously at removing them. In a statement, the council said.

“We understand the historic significance of the Biggleston lampposts in Canterbury and the affection residents have for them. However, recent safety inspections have revealed serious structural issues which mean the lampposts can no longer be considered safe.

“The cast iron columns have failed structural tests carried out at the base of the column, confirming internal corrosion and other defects”

Naturally, no one wants to walk on a dangerous street. But why not simply repair the existing lampposts then? They have been around for several decades at this point. However, the relevant cost would be too much, so claims the council.

“The original factory that produced these lampposts has closed, and the moulds used to make them no longer exist.

“Recreating these moulds and manufacturing new cast iron lampposts, or refurbishing the existing lampposts would not be the most effective use of limited maintenance budgets, given other higher-priority needs.

“It is anticipated that creating a bespoke mould alone would cost tens of thousands of pounds, and each new cast iron column could cost in excess of £5,000. By comparison, installing a modern steel lamppost costs about £168.”

So in the grand scheme of things, it is simply cheaper and more efficient to replace the Biggleston lampposts with something modern. A common problem across many sectors at the present time.

Ptolemy Dean, president of the Canterbury Society and the surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey, spoke to the Independent about this issue.

“It’s synonymous with a problem that is right at the very heart of everything that’s going on in the local environment at the moment, which is that no one can maintain anything, no one will, every, the budget for cutting is maintenance, and therefore you’re left with replacement as the solution,

“It’s really, catching up on us now. Years of, years of austerity and the Canterbury thing is the latest in this story.”

So that is what is going on with Canterbury, but what does this have to do with Pluribus?

Plubrius is a science fiction series centred around Carol Sturka. A romantasy novelist who, after a bizarre virus from space turns nearly everyone on earth into a strange hive-mind, seems to be very nearly all alone in the world.

In the series by the creator of Breaking Bad, Ms Sturka is one of only 13 people globally who have managed to retain their individuality. Everybody else is controlled by a single shared consciousness who continue to live and work in the world around them. Much of said work seems to be centred around keeping Carol, and the other twelve ‘unjoined’ people as ‘happy’ as possible, as well as investigating a way to change the virus to bring Carol and the others into their mental melting pot.

The series at certain points exposes us to bizarre scenes about the lengths and efforts the ‘joined’ will go to in order to make Carol happy, including an entire section where they work to stock and operate an entire supermarket for use by her and her alone.

Why is she the only one using it? Because everyone else’s nutrition is handled very differently, and much more ‘efficiently’ as the series explains. Efficiency is at the heart of much of what the ‘joined’ do, with them even going so far as to all sleep in large enclosed indoor spaces like stadiums and concert halls, as it’s cheaper to heat and cool one large room instead of hundreds of small ones.

While the series itself generally focuses on Carol’s character dilemma and the different reactions of other members of the remaining 13 to the strange global situation, an underlying question is asked by the ‘efficiency’ and ‘energy saving’ efforts of the ‘joined’.

Efficient to do what? What are you doing with all that saved energy? That saved space? That saved effort? What is the purpose at the heart of the plans of the ‘joined’?

This same question could be very legitimately be asked of the Reform run Kent County Council. Yes, they can save a fair amount of money on the new lampposts being replaced in the city centre – approximately £4,832 at the low end.

But why?

What are they going to do with the money they save?

Councils and governments of all stripes are always going to have an answer to this question. There are any number of services and programmes and initiatives and efforts that will need money. Everything from potholes to playgroups, care homes to council events. There will always be some reason and somebody else who could need money somewhere. Which means, for things like lampposts, sometimes the most functional options must be chosen.

There are two problems with this. First if ‘functional’ is all we ever spend money on, then ‘functional’ is all we will ever be.

Is that all we want for our cities and town centres. Functionality? A place where it is just easy to function in.

Second, there is the ‘saddest man in the world’ problem. Someone might be sad about the loss of the pretty lampposts, but someone else might be sad that their car has lost a tyre because of a pot hole, but someone else is sad because their friend has lost an arm because of being homeless and getting gangrene from a cut on a paving slab, but someone lese might be sad because their entire families home burned down and…

This is what’s known as the fallacy of relative privation. The argument that since there are worse problems out there, only the worst of the very worst should ever actually take our resources.

But if that is all we ever do, what else will we do?

Maybe in a world where everyone’s mind is linked, this could work. But outside of such a world, it can’t. People will always disagree, and problems and issues of smaller order will still need addressing.

Do we really want a world of “efficiency” where the artistic and beautiful is lost simply because we can’t be bothered to pay to maintain it?

This is what both Pluribus and the Canterbury Lamppost dispute are both indirectly asking. When we are so good at saving and scrimping, when – if ever – will we spend? Are we so good at finding efficiency that we forget we also need to find joy? Even, nay especially, when we work in local government.